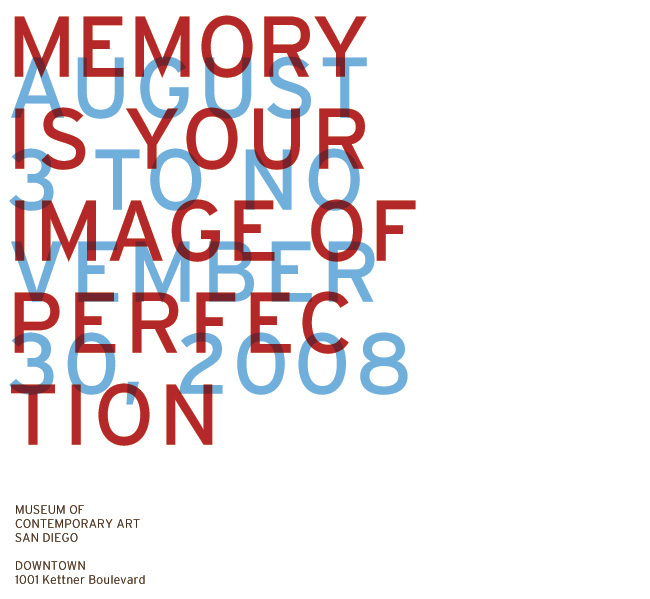

Memory Is Your Image of Perfection explores the subject of memory through connections, oppositions, and overlaps among the work of 14 women artists who currently live in or have been associated with Southern and Baja California. The exhibition—which takes its title from a photograph by Barbara Kruger—researches photography and video from MCASD’s collection by Eleanor Antin, Uta Barth, Andrea Bowers, Anne Collier, Jeanne C. Finley, Barbara Kruger, Suzanne Lacy, Sharon Lockhart, Ana Machado, Sherry Milner, Cindy Sherman, Taryn Simon, Yvonne Venegas, and Carrie Mae Weems, with additional pieces by invited artists Kerry Tribe and Susan Silton from Los Angeles, and Alicia Tsuchiya from Ensenada.

Often driven by feminist critique of the visual languages and politics of representation, these artists have expanded the usages and limits of photographic media. They have exploited the possibilities opened by the gap between documentary uses of photography and the artists’ desire to apply this medium to the expression of a variety of individual and subjective points of view. The works presented in the exhibition share strategies that take advantage of the ambiguities built into photography, film, and video as visual languages deeply implicated with subject matter related to the capture of time, documentation, and memory.

Sharon Lockhart

Enrique Nava Enedina: Oaxacan Exhibit Hall, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, 1999.

three framed chromogenic prints, edition 1 of 6.

Museum purchase, Contemporary Collectors Fund.

Photograph by Pablo Mason.

Artworks in the exhibition range in style from straight documentary photography—of which journalistic photos are the most widespread examples—to manipulated photography—today dominated by the use of digital computer programs. While artists like Sharon Lockhart, from Los Angeles, and Yvonne Venegas, from Tijuana, address the tradition of straight documentary, they make their personal involvement with the subject visible to demarcate their departure from orthodox documentary processes that suppose objectivity in relation to the subject. Lockhart’s triptych, Enrique Nava Enedina: Oaxacan Exhibit Hall, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City (1999) represents the space of the museum as a place where cultural meaning is produced but makes a point to locate that site within a cultural matrix that includes labor and economics. Best known for producing works in series that develop slowly over time after intense research, Lockhart plays with the tension between analytical distance and subjective empathy. The triptych shows a masonry laborer, Enrique Nava Enedina, working within a glass structure that shields the precious historical artifacts from the dust he is producing. The subject is caught three times as he progresses in this task, an evolution that also demarcates his gradual objectification as Nava Enedina appears to become another item of display encased in museum furniture similar to that which houses the anthropological artifacts on view. In spite of the formality of the photographic presentation, Lockhart creates conditions through which viewers identify with a specific individual.

Yvonne Venegas—an artist whose long-term project Las novias mas bellas de Baja California (The Most Beautiful Brides of Baja California) is also a series that has resulted from prolonged involvement with her subject—creates the appearance that she simply captures unguarded snap-shot moments caught by chance. Venegas delves into the Tijuana middle-class to which she belongs, focusing especially on women at weddings, showers, baptisms, and birthday parties. Seen as a whole, the series documents an insider’s view of class and gender in a specific context. Although Venegas avoids passing judgment on her subjects’ lives or on the system into which they are born, her work reveals with surprising clarity the gender roles and class dynamics at work in that society. She is both detached and involved in her subject matter in a way that complicates her use of documentary or journalistic styles—making her both an observer and participant.

Yvonne Venegas

Consuelo, 2001.

chromogenic print.

Gift of Gough and Irene Thompson in gratitude to Hugh M. Davies and Lynda Forsha.

Histories of the development of photography from the second half of the 1960s onwards describe the evolution from dominant documentary genres, assumed to be more realistic and truthful, to conceptual photography, in which photos were used as artless records of ephemeral actions and performances that were often the true moments of artistic intention. Conceptual photographers chose to adopt a “style-less” approach often derived from deadpan travel photography and mail-order catalogues1.

Through a variety of media that includes photography and video to record ephemeral performances, San Diego-based artist Eleanor Antin has explored the relationship between fact and fiction in storytelling and art-making. In 1971 she conceived her graphic novel 100 Boots, which follows the adventures of a character (100 rubber boots) from a pastoral life in the hills of Solana Beach, to unemployment, war, and to their own exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Antin mailed 51 photographic postcards for a period of two years to about 1,000 “art world” people—artists, poets, writers, critics, curators, museum directors—as a strategy to intervene into the existing art market and distribution systems. Antin, who did not take the photographs herself, applied the conventions and format of serialized, travelogue essays—already used for conceptual purposes by, among others, Ed Ruscha—to capture the performance of her hero’s adventures. In other works of the same period, Antin herself took on personae that were photographed or filmed during performances created only for the camera. In 1975, New York artist Cindy Sherman began a series while still a graduate student at SUNY Buffalo that took the form of fictional film stills and paralleled Antin’s strategies. Untitled (1975) is an early example of Sherman assuming the identity of a demure Cold-War mother in a typical 1950s film pose.

Eleanor Antin

100 Boots, 1971-1973.

fifty-one postcards.

Museum purchase.

Photograph courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Photographic pieces like those by Antin and Sherman depend on a paradoxical use of the medium to create a kind of false memory of something that occurred only as a dramatic act. This theatrical ruse exists for the camera as a way to self-consciously construct an image that, by virtue of its convincing similitude to “reality,” is legitimized beyond the original fictional act by its photographic existence. Up to the 1960s, most photographic styles, including documentary and conceptual forms, functioned on the assumption that the mechanisms of representation that generated the image are transparent; in other words, the photographer’s own intellectual and emotional filters did not affect the image itself in the same way that the hand of the artist is everywhere present in painting. Antin and Sherman created photos that foreground their author-ial intent and the construction of their images even while the camera that created the image remained untouched by their hand. Authorship in these works is very much apparent in their ability as actresses to “truthfully” become another person. Their works prove that photography is a very powerful way to memorialize even fictional events and to confer on this fiction the mark of reality by virtue of it having been photographed. Similarly, a work that addresses the role of photography as false evidence is New York-based artist Taryn Simon’s powerful Frederick Daye, Alibi Location, American Legion Post 310, San Diego, CA (2002). This print is part of The Innocents series created in 2002 when Simon traveled across the United States to photograph and interview men and women who had been convicted for crimes they did not commit. In each case, photographs were the main source of misidentifications and false memories that led to convictions which were later repelled when these documents were disproved.

From their inception, photographic genres, including film and video, have been considered the most direct and efficient means of recording the present. Reality is copied or reproduced as a virtual image that has a much longer existence in time than the source. Photography’s value as a document is linked to its faithfulness to the source. Nevertheless, we cannot ever fully examine the image’s accuracy because its authenticity is tested in relation to how well it represents moments that remain only recollections. At their simplest, photographs, film, and video document memories: likenesses of beloved family members; important events; politically relevant moments. The widespread reliance and trust in photographic mechanisms to record without altering, and then to reproduce reality, speak to a shared anxiety over forgetting. These devices capture time and verify that our memories do not lie. Cameras provide relief to a permanent condition of inevitable amnesia because all events can be fixed into an image or series of images that confirm that something did occur; that we were there to record it; and that time’s inexorable passage has, for a moment, been stopped.

Issues of remembrance are essential to photography as artistic medium. Memory remains the principal test of the medium’s representational accuracy; it is also that which makes photography responsive to artistic intention and something other than a purely scientific recording device. This is because the mechanisms by which we understand phenomenal experiences are dependent on systems of encoding, storage, and retrieval that are often more revelatory of who we are at the present moment than of what occurred in the past. Each person has unique experiences and neurological apparatuses that interact with the various instruments of memory to form individual psychology—essentially to inform subjectivity.

The confrontation between our expectations on photography as a realistic record of the past, and the subjectivity of memory, introduces a fissure into the medium’s apparent representational accuracy that is unstable enough to allow for a wide variety of desires and interpretations. Under these conditions, photographic media are revealed to no longer be, even at their most documentary and scientific, direct records of past moments but are open to constant interpretation both by author and audience. Los Angeles artist Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Memory Is Your Image of Perfection) (1982), for example, examines how even seemingly “neutral” forms of photographic representation, such as medical imaging, encode male and female readings and points of view. This manipulated photograph is created by overlapping text unto an appropriated x-ray image of a skeleton immediately identified as a woman by the outlines of stiletto heels, bracelets, and a diamond ring. Kruger’s textual addition to the x-ray urges the viewer to understand “your image of perfection” as a process of recalling that is the product of a culturally determined construction of femininity and identity evidently external to the photographic image itself.

Barbara Kruger is part of a generation of artists who identified themselves as Feminists and who actively question women’s representation in mainstream culture. Emerging in the 1980s, Kruger critiqued photography’s documentary accuracy by questioning the impossibility of understanding anything, photographs included, outside of a defining context. She used the medium as a site of intervention and manipulation through appropriation techniques that relied on creating photographic works by taking pre-existing images, “the value of which might already be safely ensconced within the proven marketability of media imagery,”2 and re-formatting them to new ends.

Kruger’s Untitled demarcates a dividing line in this exhibition between artworks that remain within a tradition of unadulterated photography and those that mix genres and approaches appropriated and cited from a variety of sources in order to give a personal reading embedded in historical documents or images. Susan Silton’s photographs—in which high-key, nearly Op-Art, stripes are overlaid on 1950s atomic cinema stills found at thrift shops around Los Angeles—are closely aligned with Kruger’s appropriation strategies. Silton’s gesture of mixing a found photo-still of a genre of apocalyptic film that responded to U.S. fears during the Cold War, is a reaction to the culture of paranoia generated in the wake of September 11th. The stripes, which hide the still photo and also create visual noise over it to give a sense of anxiety, reference the use of striped tarps over termite-infested homes under fumigation; a metaphor for the covert disintegration of American civil liberties during the Bush presidency.

Susan Silton

The Day the Earth Caught Fire from The Day, the Earth, 2006.

chromogenic print.

Courtesy of the artist and SolwayJones, Los Angeles.

Photograph courtesy of the artist and SolwayJones, Los Angeles.

Images that refer the viewer to collective memories and to specific historical scenarios are essential to Silton’s work and to its articulation of an actively political position that evidences her critical intentions in the present. The same is the case with Andrea Bowers’ single-channel video, Letters to an Army of Three (2006). The Los Angeles-based artist uses aesthetics to address activist politics as a subject and also as a source of inspiration. She questions the neutrality of film in her beautiful memorial to the Army of Three—three suburban women who crusaded for legal abortions and women’s health rights from 1964 to 1973, thus founding the pro-choice movement in the United States. The work weaves together portraits of women and men reading the poignant letters originally sent to the Army of Three asking for information and support. Each reader is seated on a stool before a neutral background in a repeated exercise that brings attention to their empathetic connection with the writer of the pleading letter. Each portrait fades to a simply composed flower still-life that emphasizes the reader’s controlled performance and embodies the absence on screen of the original letter-writer. Bowers interjects forms of identification that rely on empathy and subjectivity between the subjects of her film—those who wrote the letters now kept in the archives of the Army of Three—and the people who perform their roles through words and actions that memorializes even as they become thoroughly present to our everyday experience.

Andrea Bowers

Letters To An Army of Three, 2006.

single channel video on DVD, edition 2 of 5.

Museum purchase, Elizabeth W. Russell Foundation Funds.

Ana Machado

Coca Cola en las Venas, 2000.

video on dvd, edition 2 of 3.

Gift of the artist.

Photograph by Pablo Mason.

Ana Machado, originally from Tijuana and currently a resident of Los Angeles, and Alicia Tsuchiya from Ensenada, also claim a heightened emotional connection to create their own very personal memorials. Machado’s expressionistic video Coca Cola en las venas (Coca Cola in My Veins) (2000) portrays her family and her experience as inhabitants of the border region of San Diego and Tijuana. Tsuchiya’s photographic narrative of the Picture Bride series (2007-08) reflects on her Japanese-Mexican family through a series of digital photos that together reveal the life and affections of her Japanese-born grandmother, who came to Ensenada in the 1920s as the mail-order-bride of a Japanese fisherman. Machado’s video uses a synchronic mix of documentary footage, found photographs, advertisements, artwork she made during art school, and raucous music. The effect is disorienting but could accurately describe what it might feel like to be from two different cultures and belong fully to neither. Yet, while both projects hinge on identification with their individual subjects, the viewer can only conjecture what those experiences were really like. Machado and Tsuchiya’s artworks are clearly about what the artists perceive about their subjects based on personal memory and point to the difficulty of telling a story objectively.

The impossibility of finding images to appropriately describe what can only be accessed through memory is the subject of Kerry Tribe’s video and photography work. Northern Lights (Cambridge) [Aurora Boreal (Cambridge)] (2005) is the first of a series of three related works that attempt to bring the past into the present as translated by the slippery processes of memory. This is a three-part installation that consists of a moody 16-millimeter film and two photographs. The film appears to capture images of the Northern Lights. Yet, while it is nowhere textually or verbally clarified, the Northern Lights images are simulated by a Lumia Ori, a kinetic work of art from the 1980s that resides in Tribe’s parents’ home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and which had caused her to form a false memory of experiencing the Northern Lights in person. The two photographs, shown in proximity to the projection, represent the objects that actually make the images and sounds in the film: one is of the actual Lumia Ori, that when turned on, generates the strange, luminous images that pass for Aurorae Borealis, and the other photograph is of a Lyricon, a musical instrument that employs optical sound technology similar to the one that is played on the soundtrack to the film by composer Jorrit Dijkstra. Northern Lights is built on a series of associative clues that mirror the apparently arbitrary associations made in memory itself. For Tribe, this work functions as an evocation of the emotional aftereffect of a particular memory and the difficulty in trying to find a way to express fully its intellectual and psychic profile.

The works in Memory Is Your Image of Perfection together reveal that the associations between photographic media and its function as mnemonic device, as evidence of the past, are what gives photography its cultural authority as record of who we are as a society at any particular moment. Nevertheless, the power in photographic imagery may come not from its representational accuracy but from its ability to express who we think we are, what we choose to see and remember, and also what we choose to forget.

Lucía Sanromán

Assistant Curator